Responding to Emergencies

Recognizing Emergency Situations

- Part of working on a ship is being cognizant of what may present a danger to the ship and its crew. Some emergencies include:

- Noticing that the ship is dragging anchor

- Noticing that mooring lines have parted

- Finding a crewmember that has had an accident

- Finding a fire onboard

- Persons fallen overboard

- Imminent threat of collision

- Noticing water ingress through the hull or that the bilge levels are higher than usual

- Noticing an oil leak

- Noticing a distress signal from another vessel

- These are just some of the emergencies that can occur on a ship. In all of these cases, the first response should be to notify the bridge. Once notified, they can begin alerting and tasking the rest of the crew appropriately.

- An oil leak may not seem like an emergency, but it could represent the early warning signs of engine or hydraulic failure. On top of that, oil on a deck can immediately become a tripping hazard and will need to be cleaned.

- Responding to shipboard emergencies requires the effective communication of orders as well as crewmembers ability to understand and carry out orders. Keep in mind that miscommunications are much more common when the crew is under pressure or in a rush.

Man Overboard Emergency

- In the case of a man overboard emergency, the first person to have visual confirmation of someone in the water is to loudly shout “MAN OVERBOARD” followed by which side of the ship.

- The initial reporting party is to never take their eyes off of person and they are to being pointing with their outstretched arm, preferably from a forward deck where they can be seen from the bridge.

- Other crew members can assist by ensuring the bridge is made aware of the emergency, that liferings or other immediately available floating equipment is deployed in the vicinity of the person in the water, and that any pointing coming from the reporting party is relayed to the bridge.

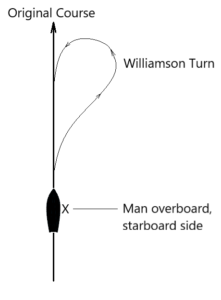

- On larger vessels, the navigating officer on the bridge may opt for a Williamson turn. This turn is meant to immediately turn the ship towards the side the person fell off so as to ensure that the propellers at the stern are well clear of the person in the water. After making this alteration, the ship is to turn in the opposite direction to bring the ship about on a reciprocal course and begin recovery operations.

Sounding the General Alarm

- A general alarm on a ship should be sounded in emergency situations when the safety of the vessel and its crew is at risk. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) sets out the requirements for when a general alarm should be sounded.

- According to SOLAS, a general alarm should be sounded when there is a risk to the safety of the ship or persons on board due to:

- Fire

- Collision or grounding

- Flooding

- Structural failure or damage

- Explosion

- Piracy or other security threats

- Once the general alarm has been sounded, the general alarm control panel that is typically located on the bridge allows officers to determine where the alarm came from.

- In addition to these specific situations, the captain of the ship may sound a general alarm in any emergency situation where the safety of the vessel or its crew is at risk. This should be done in conjunction with a ship-wide announcement as to the nature of the alarm.

- When the general alarm is sounded, it should be loud enough to be heard throughout the ship, and crew members should immediately respond according to the emergency procedures outlined in the ship’s safety management plan. This may include donning life jackets, mustering at assigned locations, and preparing lifeboats or other survival equipment.

- Although it isn’t mentioned in SOLAS, if the ship’s general alarm makes use of the ship’s whistle, it’s common for the general alarm to be a continuous sounding of the ship’s whistle for at least 10 seconds.